ACL Reconstruction (Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Graft)

ACL reconstruction is a surgical procedure that is typically performed arthroscopically in order to replace a damaged ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) with graft material, either from the patient’s own body (autograft) or from a donor (allograft).

Key statistics about ACL Reconstruction

- 100,000 – 200,000 ACL tears and sprains occur in the United States each year[1]

- Approximately 100,000 ACL reconstruction procedures are performed in the United States each year[2]

- 90% of patients who undergo ACL reconstruction have near-normal knee function restored[1]

- 81% of patients who undergo ACL reconstruction return to some form of sport, 65% return to their preinjury level of sport, and 55% return to competitive sport following the procedure[3]

Expert Insights

Selecting the right types of ACL Graft - Daniel Cooper, MD

Why is ACL Reconstruction performed?

ACL reconstruction is often required to relieve pain and restore knee function after a severe sprain or tear to the ACL.

It is common to hear or feel a popping sensation when the ACL is torn, and the injury is often accompanied by rapid swelling, severe instability, intense pain, and loss of range of motion. An ACL tear also may increase the likelihood of sustaining further damage, such as a torn meniscus.

Who needs ACL Reconstruction?

The ACL is the most frequently damaged ligament in the knee.

A partial or complete ACL tear is a common injury that often occurs due to sports-related trauma, or from activities that involve sudden stops and changes in direction, or forceful twisting. Football, basketball, and soccer players, as well as skiers are among athletes most at-risk for ACL tears.

ACL reconstruction is necessary to address ACL tears that cannot be repaired or treated with nonsurgical measures.

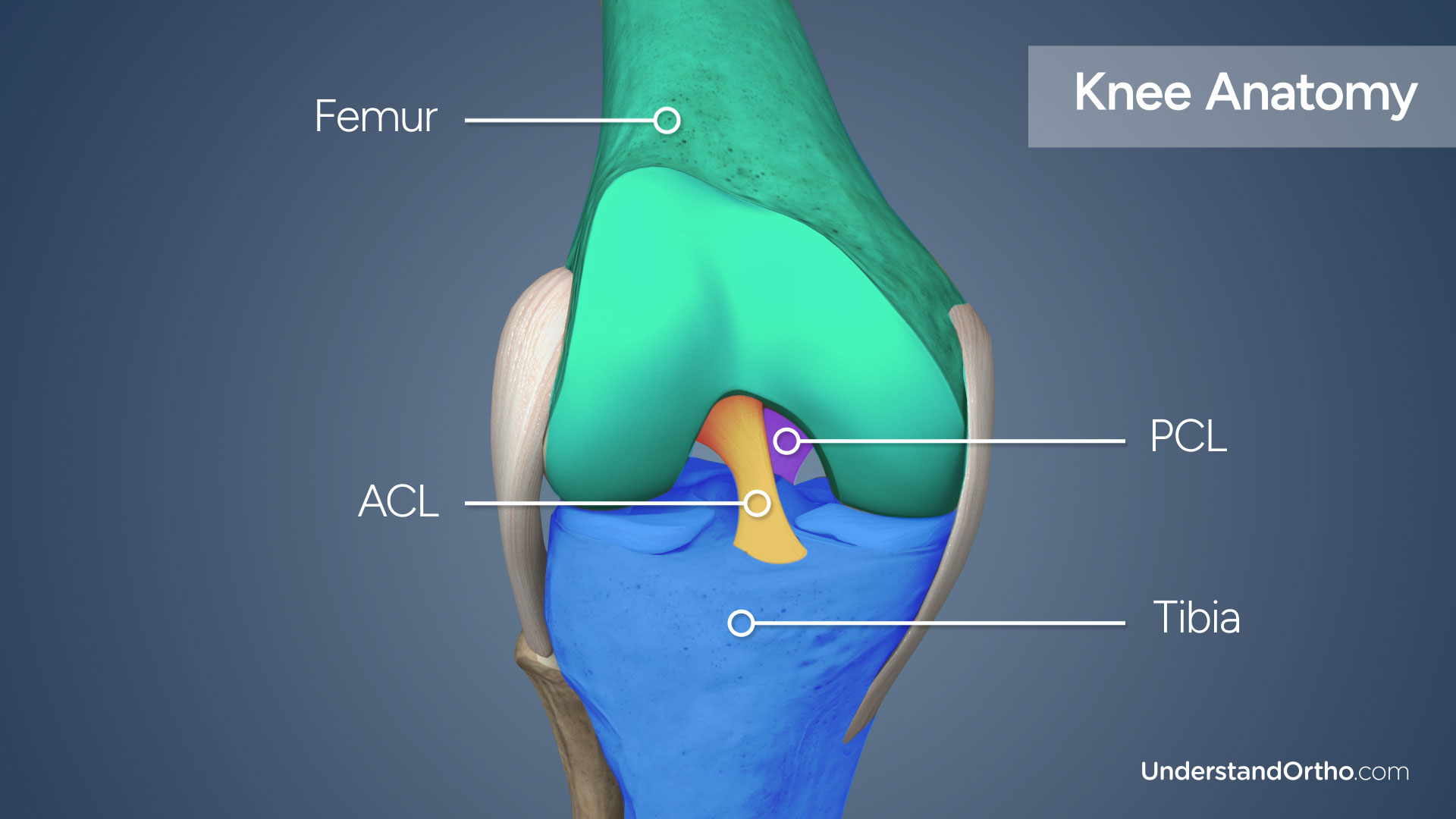

Knee Anatomy

The knee joint is formed by three bones: the femur (thigh bone), the tibia (shin bone), and the patella (kneecap).

Ligaments connect bones to other bones and provide stability to the joint. There are two cruciate ligaments located inside the knee joint that connect the femur to the tibia: the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). The ACL and PCL cross each other and work together to control the forward and backward movement and limit rotation of the knee.

How is the Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Graft prepared?

There are numerous graft material options available for ACL reconstruction, which are either autografts (from the patient) or allografts (from a donor). These include:

- Bone-patellar tendon-bone graft

- Hamstring tendon graft

- Quadriceps tendon graft

A bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft is the graft preferred by many surgeons for young, active patients with torn ACLs.

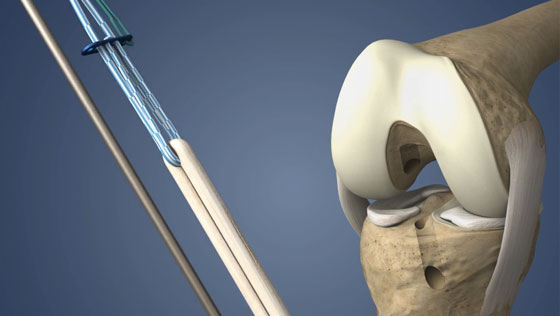

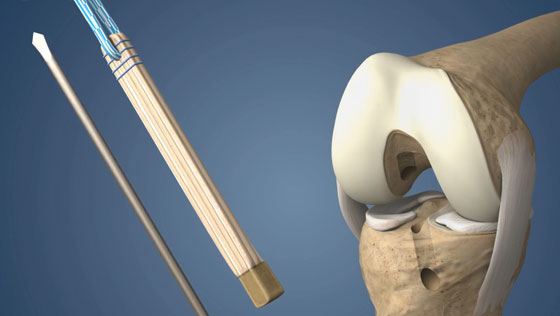

The middle portion of the patellar tendon (the tendon attaching the patella to the tibia) is harvested during the reconstruction procedure. A bone-tendon-bone graft contains a bone plug at each end, which is used to anchor the graft in place.

How is ACL Reconstruction using a Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Graft performed?

- The surgeon will make small incisions around the knee joint and the arthroscope will be inserted into one of the incisions.

- Saline solution is pumped into the joint to expand it and improve visualization.

- Images from the arthroscope are sent to a video monitor where the surgeon can see inside the joint.

- The damaged portions of the ACL are removed and the bones are prepared for the graft.

- Using a drill, a bone tunnel is created in the femur and tibia.

- After the graft is harvested and prepared, it is pulled through the femoral and tibial tunnels and the ends of the graft are secured with screws or other fixation devices.

- Over time, the bone plugs on the ends of the graft are incorporated into the surrounding bone.

- Finally, the saline solution is drained, instruments are removed, and the incisions are closed using sutures.

What are the risks of ACL Reconstruction with a Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Graft?

Risks associated with ACL reconstruction may include:

- Infection

- Blood clots

- Knee stiffness

- Limited range of knee joint motion

- Pain over the kneecap

How long does it take to recover from ACL Reconstruction?

-

24 hours after surgery

Physical therapy will begin and pain killers may be prescribed. -

1-3 days after surgery

Most patients are discharged from the hospital and will be able to walk with crutches. A physical therapy routine will be established by the surgeon and physical therapist. -

2 weeks after surgery

Any non-dissolvable sutures are removed, and bruising and swelling begin to subside. -

3-6 weeks after surgery

Most patients are able to return to work and resume driving and most daily activity. -

8-12 months after surgery

Most patients are fully recovered from ACL reconstruction.

What are the results of ACL Reconstruction?

ACL reconstruction is a safe and effective procedure performed to restore knee function following an ACL tear. 90% of patients who undergo ACL reconstruction return to near-normal knee joint function[1] and 81% return to some form of sport[3] following the procedure.

Find an Orthopedic Doctor in Your Area